What's in a Name: The Kikuyu Tribe of Kenya

Introduction

The Kikuyu tribe, known as the Agĩkũyũ, is the largest ethnic group in Kenya, comprising approximately 17.13% of the nation's population, with an estimated count of 8,148,668 individuals. Predominantly found in the Central Kenya region, they inhabit counties such as Kirinyaga, Nyeri, Nyandarua, Murang’a, and Kiambu. The Kikuyu landscape is characterized by the majestic Mount Kenya, which rises to 5,199 meters, and the Aberdare mountain range, reaching over 3,999 meters. The peaks of Mount Kenya are considered sacred, believed to be the dwelling place of Ngai, the Kikuyu God, revered by the community.

The Kikuyu language, known as Gikuyu or Gĩgĩkũyũ, is part of the Bantu family and features at least five distinct dialects. Among the Kikuyu, there is a strong connection to the Embu and Mbeere communities, sharing linguistic and cultural ties. The Kikuyu naming system is particularly noteworthy for its simplicity compared to other ethnic groups in Kenya, as detailed in the sections below.

Language and Identity

Kikuyu, also called Gekoyo, Kuyu, Gigikuyu, and Gikuyu, is primarily spoken in the Central Province between Nyeri, Kirinyaga, Kiambu, Murang'a, and Nyahururu, extending to areas like Nairobi, Nakuru, and Laikipia. The language has four mutually intelligible dialects: Kirinyaga, Muranga, Nyeri, and Kiambu, with additional regional variations.

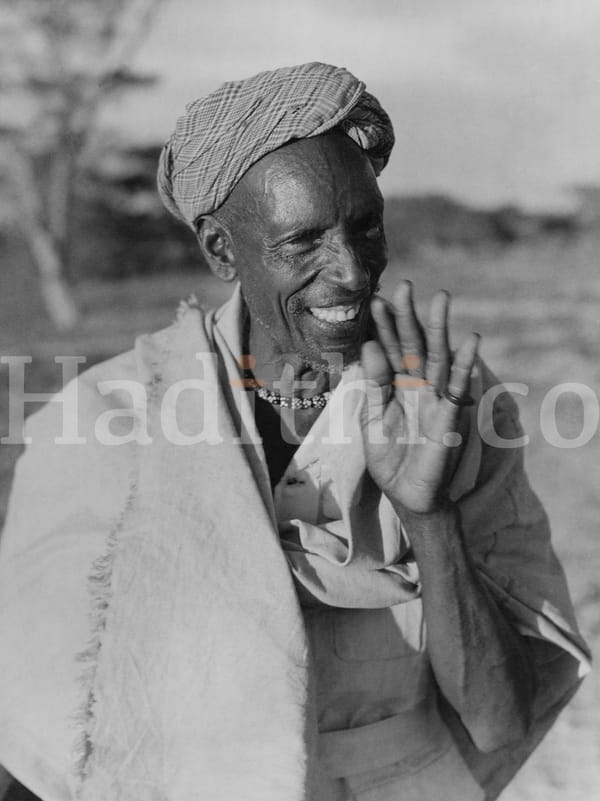

Mr. Kaburi, a local elder, shared insights about Kikuyu characteristics. He noted that a Kikuyu person is often perceived as clever, with the term "mugikuyu" derived from "muugi," which connotes intelligence. Generosity is another hallmark of Kikuyu identity, a trait they attribute to their creator, Ngai. The name "mugikuyu" also connects to “mikuyuuni,” meaning the fig tree, which symbolizes sustenance and divine promise. Kikuyu culture emphasizes family and community, with the extended family unit, or mbari, playing a crucial role in social structure.

The Kikuyu Naming System

Significance of Naming

In Kikuyu culture, naming is a significant process, believed to connect children with the spirit of their ancestors. Children are often named after relatives to honor family lineage and preserve identity. For instance, when a grandmother greets a child named after her deceased husband, she might say, “Wakia atia murata,” meaning “Hail! My lover,” indicating the belief in spiritual reincarnation.

The Kikuyu naming convention is systematic. Upon marriage, a woman adopts her husband’s last name.

Children are named according to both patrilineal and matrilineal lines, with the first boy named after the paternal grandfather and the first girl after the paternal grandmother. Following children are named alternately after maternal and paternal grandparents, reinforcing family identity. The second daughter is often named Muthoni, meaning "respectful," reflecting familial relationships. Additionally, children receive a "given name" based on observable traits.

Naming Patterns and Their Cultural Significance

The Kikuyu naming system is rooted in a lineage framework that maintains ancestral connections. The firstborn son is named after the paternal grandfather, the firstborn daughter after the paternal grandmother, and subsequent children alternate between the maternal and paternal sides. This practice not only preserves family identity but also ensures the continuity of cultural memory.

Names often reflect circumstances surrounding a child’s birth and embody aspirations or qualities desired by the family. The collective process of naming involves elders and community members, emphasizing the communal nature of identity formation. Names can also indicate clan affiliations, with specific prefixes identifying membership in particular clans, strengthening kinship ties.

The Kikuyu naming system has evolved in response to external influences, such as colonialism, which introduced European names. In contemporary society, many Kikuyu individuals adopt dual naming practices, using European names in public while preserving indigenous names in private. This duality reflects the resilience of Kikuyu cultural identity in the face of historical challenges.

The Importance of Naming Among the Kikuyu

The act of naming among the Kikuyu is deeply embedded in cultural, spiritual, and social contexts. Names are not mere identifiers; they encapsulate values, beliefs, and aspirations of the community. The naming ceremony is a momentous social event that formally welcomes a newborn into the family and community, establishing their lineage and social role.

Central to Kikuyu naming is the connection to ancestors. Names often honor deceased relatives, with the belief that the spirit of the ancestor may reincarnate in the child. This connection is so profound that older women may greet a young man named after a late husband with affection, acknowledging the spiritual presence of the ancestor.

The structured naming system reinforces family identity and kinship. Subsequent children are named after the grandparents' siblings, ensuring continuity across generations. Names also reflect the child’s birth circumstances or desired traits, highlighting the Kikuyu's deep connection to their environment.

The practice of naming is a communal process, involving elders and family members, signifying acceptance into the community. Names carry clan affiliations, with prefixes indicating membership, reinforcing social cohesion. Despite the influence of colonialism, the tradition of naming remains a vital cultural practice, affirming connections to indigenous heritage.

Birth Rituals Among the Kikuyu

Pregnancy Rituals

In Kikuyu culture, pregnancy is marked by specific traditions. Upon learning of a pregnancy, a woman alters her diet, consuming mashed foods such as bananas (marigu), black beans (njahi), arrow roots (nduma), and sweet potatoes (ngwachi). As delivery nears, her diet becomes restricted to milk and flour, avoiding meat and vegetables. A midwife plays a crucial role, massaging the mother's abdomen to facilitate labor and delivering the child, traditionally excluding the father, who is considered to be in a state of taboo (thahu) during birth.

The arrival of the baby is announced by birth attendants who ululate four times for a girl and five times for a boy. This custom symbolizes the sacred number nine, significant to the Kikuyu. After birth, the mother screams to announce the child, and the placenta is treated as a sacred symbol, buried in an uncultivated field to symbolize fertility.

Post-Birth Rituals

Following birth, the mother and child undergo a period of seclusion—four days for a girl and five for a boy—during which household activities are restricted. This period symbolizes a spiritual death and rebirth, marking the transition to a new life stage. Upon completion of seclusion, the mother undergoes a purification ceremony, including shaving her hair, which signifies readiness for future children.

Naming occurs shortly after birth. The firstborn son is named after the paternal grandfather, while the firstborn daughter is named after the paternal grandmother, with subsequent children following the same pattern. The father enhances his status by ensuring proper naming, symbolized by placing a goatskin wristlet on the child's arm, linking the child to the community and ancestors.

At around five or six years, children undergo ear-piercing in a ceremony called gutonywo matu, marking their eligibility to care for goats. Before initiation through circumcision, children must experience a ritual known as "the second birth" (kuciaruo keri), symbolically returning to the womb for full community participation.

Consequences of Failing to Undergo the Second Birth

If a child does not undergo the second birth ceremony, they are not considered a full community member, facing social and spiritual restrictions. This includes being barred from key rites of passage, inheritance, and communal rituals, as the second birth is essential for transitioning from infancy to active membership in Kikuyu society.

The Kikuyu Creation Theory

The Kikuyu creation myth centers on Ngai, the creator who formed the first man, Gikuyu, and woman, Mumbi. They are considered the ancestors of the Kikuyu people. According to tradition, Ngai allocated land to Gikuyu on the southwest slopes of Mount Kenya, where Gikuyu established a homestead near Mukurwe wa Nyagathanga, a sacred site filled with fig trees.

Gikuyu and Mumbi were blessed with nine daughters, whose names—Wanjiru, Wambui, Wanjiku, WaNjeri, Nyambura, Waithira, Wangare, Wangui, Wairimu, and Wamuyu—are still widely used today. These daughters represent the foundational figures of Kikuyu clans, each giving rise to a distinct clan.

When the daughters sought to start families, they asked their father to pray to Ngai for suitable husbands. Following his sacrifice under a Mugumo tree, nine men appeared, marrying the daughters and establishing the origins of the Kikuyu clans.

Clan and Family Structure

Kikuyu society is organized into clans, each tracing its lineage back to one of Gikuyu and Mumbi's daughters. Historically, the clan system was significant, though it has diminished over time. Today, family groups (nyumba) serve as the primary social units, traditionally self-sufficient and independent.

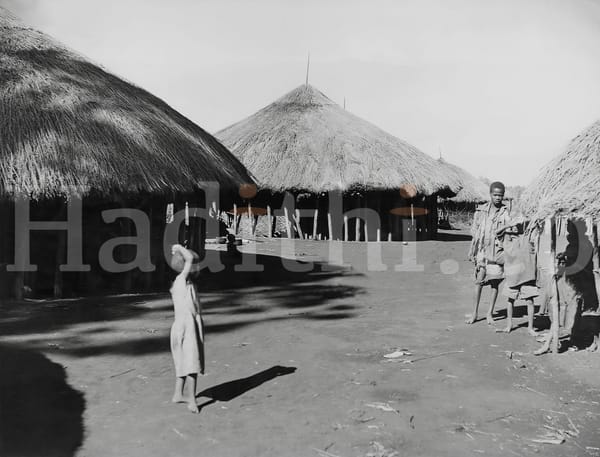

As the Kikuyu population expanded, broader social structures emerged. The homestead (mucii) comprised several families living and working together, forming a community unit called mbari. These units were connected to the nine clans, which were united by their descent from Gikuyu and Mumbi’s daughters.

Despite the historical importance of clans, Kikuyu culture has shifted towards a predominantly patrilineal structure. The age-set system, known as mariika, remains significant in uniting individuals across clans, with members sharing responsibilities and social duties.

Life Stages (Marika)

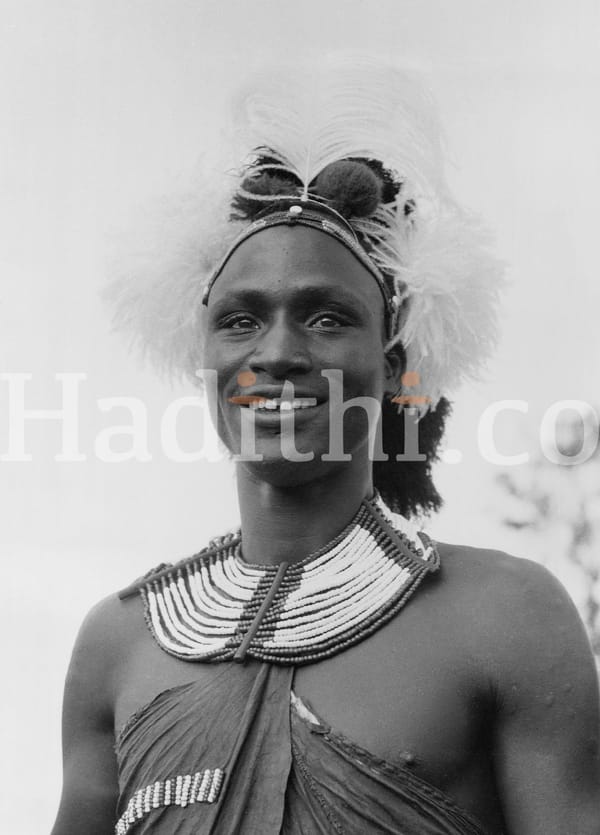

The Kikuyu age-set system, mariika, categorizes individuals based on circumcision and age. This system historically served as the primary political institution, initiating groups of boys annually into generation sets that held leadership roles for decades.

Each age set holds a common name reflecting significant events or characteristics. Although the age-set name isn't typically used as a personal name, the legacy of groups like "Maina" and "Mwangi" informs cultural identity, linking individuals informally to their historical roots.

Kikuyu Names and Their Meanings

Kikuyu names are rich in meaning, often symbolizing traits or circumstances. Here are some common names and their meanings:

- Njoki - "Coming back"; often given to daughters born after a mother's death in childbirth.

- Muchoki - Male equivalent of Njoki.

- Wanjohi - "One who drinks beer"; named after a family member known for drinking.

- Wacira - "One who settles disputes"; associated with mediators.

- Mumbi - "Potter"; reflects creativity.

- Nyambura - "Born during the rainy season."

- Njau - "Calf"; symbolizes youthfulness.

- Ngari - "Leopard"; signifies strength.

- Muruthi - "Lion"; denotes bravery.

- Mutongu - "Rich person."

- Muthoni - "Mother-in-law"; reflects family ties.

- Mwangi - "One who wanders"; associated with exploration.

- Kiura - "Frog"; signifies adaptability.

- Wanjira - "Born by the roadside."

- Macharia - "One who searches."

- Muriithi - "Shepherd"; denotes guidance.

- Wang’ombe - "One who owns many cows"; common among pastoral communities.

- Waceke - "The slim one."

- Nyaguthii - "One who travels."

- Wamucii - "Always stays at home."

- Wacera - "Always visiting."

- Murugi - "The cook."

Kikuyu naming practices reflect cultural values, aspirations, and social structures. Names serve as markers of identity and are imbued with meanings that influence destinies, reinforcing connections to ancestors and the community.

Conclusion

The Kikuyu tribe of Kenya represents a rich tapestry of cultural heritage, deeply rooted in traditions that shape identity and community. Through their naming practices, birth rituals, and social structures, the Kikuyu maintain a profound connection to their ancestors and the land. As they navigate the complexities of modern life, the resilience of Kikuyu culture continues to be a testament to their enduring legacy. Each name, each ritual, and each story encapsulates the spirit of the Kikuyu people, preserving their history and identity for generations to come.