Mbeere of the Dry Hills: Memory, Power, and Cultural Survival in Central Kenya

Introduction

The Mbeere (Ambeere) are a Bantu-speaking people who inhabit the semi dry south eastern slope of Mount Kenya. They are largely located in what was once the Mbeere District, now a section of the Embu County; their land extends into the Tana River basin. Their culture has been shaped by their history of migration and environmental adaptation, close family relationships, ritual leadership, and political marginalization. With a terrain that is vulnerable to drought, the Mbeere have developed the strength of subsistence activities and societal groups.

In this area, the name Mbeere is understood to mean “the first.” This meaning shows a sense of being early settlers, having deep roots, and holding a rightful historical claim to the Mount Kenya region. Even though the Mbeere share similar language and culture with neighboring groups such as the Embu, Kikuyu, and Meru, they have kept a clear and separate identity. This identity developed over time as a response to harsh environmental conditions, the disruptions caused by colonial rule, and the neglect experienced after independence.

Origins, Migration, and Relationship with the Embu

The Mbeere people, the Embu, Meru, Kikuyu, and Kamba are all related to oral histories that trace them to the Bantu migrations into East Africa. These stories show layered memories of movement. Others say they arrived on the coast, which was commonly referred to as Shungwaya. Then there are other ones, who mention north, such as the Lorrian Swamp or Ethiopia, and then they moved into the Nyambene Hills. Their ancestors left Nyambene and headed southwards towards the foothills of Mount Kenya, Kiang'ombe, and Mbeere Hills. There is one tradition about the ancestral homeland named Mariguuri, or the Land of Bananas. This name suggests either an early dispersal point or a symbolic memory of fertility and abundance. Some people interpret the term Mbeere to mean first, as the community believes that they were the first occupants of their current land.

Traditionally, the Mbeere and the Embu are regarded as a single people. They had similar Bantu ancestry with shared language, rituals, and social organization. They are told orally as siblings, and connected with ancestral figures like Mumbeere and Kembu (Muembu). Their breakup is recalled in a number of stories. A popular tale tells of a mock battle that claimed lives after real swords were used instead of training sticks, resulting in a permanent split. Other reasons are concerned with struggles for resources, power, and wealth. Embu had more productive lands, and the Mbeere were being slowly relegated to dry regions. The split is associated with Igamba Ng'ombe and Thuci River that turned out to be a symbolic and geographical dividing line. Mutually used nicknames: the Mbeere were called Clan of Famine, the Embu Clan of Rebels. The ecological and social inequality between them determined their separation.

The post-separation saw the Embu moving into the slopes of Mount Kenya that were higher, wet, and more fertile. The Mbeere however were inhabiting drier and the lower altitude Kiang'ombe and Mbeere Hills that extended to Tana river. These environmental variations resulted in different lifestyles. The Embu were more concerned with agriculture, whereas the Mbeere were more concerned with livestock, drought-resistant crops, and trade particularly in times of frequent famines. The two communities maintained close social and economic relations, but they were distinguished by certain cultural and economic practices. The Embu were involved in barter trade, exchanging food for goats, animal skins, and other goods. They also maintained designated ritual spaces, such as sacred groves (matiiri), and practiced structured age-set systems that organized social roles and responsibilities within the community.

Even though the colonial rule that followed after 1906 enhanced administrative division, linguistic mutual intelligibility and longstanding cultural similarities all affirm their common origin and their ancient kinship ties.

Language and Cultural Identity

Central to Mbeere cultural identity is the Kimbeere language, a Bantu language within the Niger‑Congo family and part of the Gikuyu‑Kamba cluster, sharing a very high lexical similarity with Kiembu, meaning they have a large shared vocabulary. The Kimbeere language, which is mainly spoken in the former Mbeere District of southeastern Embu County, has a 21-letter alphabet (seven vowels, with the unique long i and u). Its phonology is also different as compared to English and other neighboring languages.

Outside of daily communication, Kimbeere serves as a source of the collective memory. It passes moral values, ecological knowledge and social norms between generations through proverbs (nthimo cia Kimbeere), riddles, folktales, ritual speech and naming patterns of its ancestors. Embedded within a patrilineal clan system most notably the Ndamata and Mururi clans, Kimbeere reinforces exogamy, inheritance customs, elder authority, and life‑cycle rituals.

Even though English and Kiswahili are gaining more ground, Kimbeere retains a crucial place in the domestic, ritual and communal setting, making the Mbeere identity a lingual and cultural unit.

Environment, Economy, and Ecological Adaptation

The Mbeere homeland, which is situated in the North and South Sub-counties of the Embu County, has varied ecological conditions that determine the livelihood and agriculture within that area. Farmers in the highlands produce bananas and maize in highlands. In the intermediate regions, the predominant crops are millet, sorghum, beans, and cowpeas. The low plains are oriented to the production of livestock, bees, and drought-resistant crops. Farming is adjusted to erratic precipitation, with a particular focus on strong and resistant food products (millet, sorghum, cassava, and legumes). Livestock cattle, goats, and sheep are traditionally a symbol of wealth and social status, and bee-keeping provides honey as food, rituals, and commerce. Economic life blends farming, herding, artisanal production, and trade. Women are in the middle of farming, pottery, basketry, and the local market, in contrast to the livestock, hunting, and long-distance exchange that is controlled by men.

In this dry area, a common cash crop that is used is khat, particularly the Muguka type, which is an important source of economic livelihood to Mbeere families. In a place with limited options, Muguka is their source of food, education, and property, and realizes the local status as Muguka means money (Mbia) and Muguka means help (Utethio). Unlike bigger leaves of Meru miraa, Muguka comprises young and tender leaves and shoots that can be harvested in nine months, hence a high-value but labor-intensive crop. Even though Muguka production and use have advantages economically, the social problems associated with this practice are school dropouts, early marriages, family instability, and absenteeism. There is also some political conflict over the crop; Muguka was banned by the Mombasa County government in May 2024, which sparked a trade war and national-level interventions, and is indicative of tensions between economic reliance, social impacts, and policies.

Clan Organization and Social Structure

Mbeere society is organized around patrilineal clans, with the three main clans being Ndamata, Mururi, and Ruku, which further branch into sub-clans such as Irumbi, Kere, and Nditi. These clans serve as the fundamental unit for social, legal, and spiritual life, regulating marriage rules, particularly exogamy, to prevent taboos, land tenure, dispute resolution, and ritual responsibilities, including initiation ceremonies that transition individuals into age sets or generation classes. Larger lineage units, such as the mcii (home), typically encompass about four generations and collectively manage land and social rights, while dispersed clan coalitions coordinate broader community interests.

Kinship and social cohesion are reinforced through cultural practices and symbolic systems. Naming conventions often reflect ancestry or circumstances of birth, strengthening identity and continuity with the past. Collective ritual obligations and ancestral commemoration maintain solidarity and reinforce shared moral and social norms. Historically, systems such as Gichiaro, or “blood brotherhood,” were used to unite separated clans, fostering a sense of unity and mutual obligation across the Mbeere community. These structures ensure that social, economic, and spiritual life remain deeply interconnected, with elders serving as custodians of tradition and enforcers of communal rules.

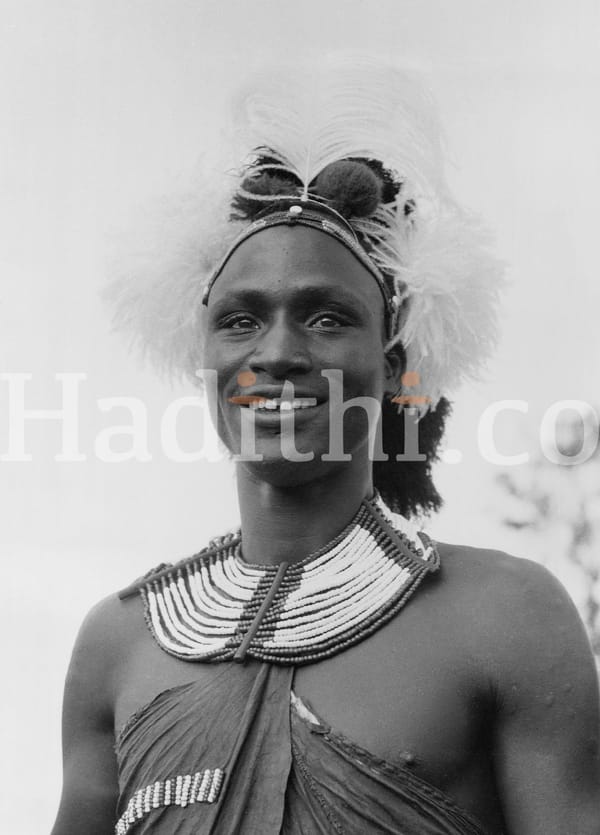

Age-Sets (Nthuke) and Traditional Governance

Traditional Mbeere society was organized around an age-set system known as Nthuke, which functioned as the central framework for political authority, ritual life, and social organization across clan boundaries. The system operated through two alternating generational sets, Nyangi and Thathi, similar to a moiety structure. A man belonged to the opposite Nthuke from his father, and his children would in turn belong to the opposing generation, creating a cyclical transfer of identity and authority. Each generation governed for approximately 25–30 years before power was formally handed over to the next through a major ceremonial transition.

These generational sets were not merely age categories but ruling bodies responsible for law-making, regulating bride wealth, overseeing initiation, conducting sacrifices, and managing sacred groves (matiiri), which served as centers of political and spiritual authority. While governance was collective, ultimate ritual prestige was sometimes associated with leading figures such as a muthamaki, and the system closely paralleled similar structures among the Embu (where equivalent age sets were known as Kimanthi and Nyangi).

The formal transfer of power between generations was marked by the Nduiko ceremony, a significant rite symbolizing renewal, legitimacy, and continuity of leadership. During this ceremony, the incoming generation ritually received authority and the “secrets” of governance from their predecessors, reinforcing accountability and institutional stability. Young men circumcised within a specific four- to five-year period formed an irua group, which later became incorporated into a broader Nthuke; as warriors, they were responsible for community defense, cattle protection, and enforcement of social norms.

Elders of the ruling generation constituted councils such as the Kiama-kia-Itura (local council) and the senior Kiama-kia-Ngome (supreme council), which adjudicated disputes, regulated rituals, and enforced customary law through sanctions that included blessings and feared curses. However, colonial intervention in the early twentieth century, particularly around the 1932 generational ceremonies, significantly weakened this age-based system by empowering appointed chiefs and integrating indigenous authority into colonial administrative structures, thereby undermining the autonomy of traditional governance.

Spiritual Worldview and Indigenous Knowledge

Cosmology and Ancestors

Traditional Mbeere cosmology centers on a supreme being Ngai or Mwenenyaga, residing on Mount Kenya, controller of rain, fertility, and moral order. Ancestors were believed to dwell in sacred forest groves and intervene in human affairs.

Death was not an end but a transition. Ancestors could bless or punish depending on moral conduct, reinforcing social cohesion.

Ritual Specialists

Spiritual mediation was performed by:

- Mundu Mugo (Andu Ago) – healers and ritual experts

- Mrathi – prophets and seers

- Munyithya – diviners

- Mrogi – feared practitioners of witchcraft

Traditional plant-based knowledge was extensive, with people relying on a wide range of medicinal plants to treat common illnesses such as malaria, fevers, and digestive problems, as well as conditions believed to have spiritual causes. This knowledge was passed down through generations and was closely linked to daily life, showing how health, the environment, and cultural beliefs were deeply connected.

Ceremonial Arts, Dance, and Symbolic Expression

Mbeere culture is richly expressed through dance, music, and symbolic objects:

- Migage (dancing sticks): associated with bravery and initiation

- Mivaru (shields): symbols of unity and protection

- Ngotho (gourd instruments): central to ritual dance

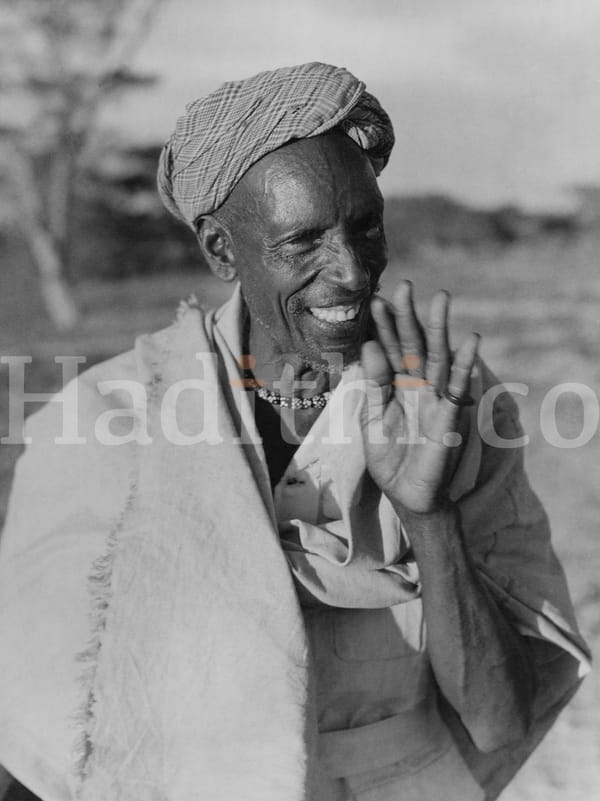

Cierume: The Dancing Warrior

One of the most iconic figures in Mbeere cultural memory is Cierume, a legendary 19th-century Mbeere female warrior and leader, who is celebrated in cultural memory for her extraordinary bravery, with her name deriving from “úrume” (fierceness or courage). During a time of frequent Akamba (Kamba) raids on Mbeere and Embu communities, when armed men struggled to defend their people, Cierume entered battle, wielding only a traditional women’s dancing stick (migage), a beaded or plain staff used in ceremonial dances. Her mesmerizing, rhythmic movements, vigorous footwork, and symbolic gestures confused and disoriented the raiders, allowing her to strike them down individually and secure victories that earned her deep respect and gratitude across the region.

Cierume’s legacy as the “dancing warrior” endures as a powerful symbol of determination, resilience, and redefined courage, inspiring Mbeere and Embu women today to blend strength, grace, and communal endurance in their own performances and lives.

The Colonial Encounter and Changing Mbeere–Embu Relations

The building up of the British colonial power in the Embu District in the early 1900s and notably after 1906 substantially changed the relationships between the Embu and the Mbeere communities. The two groups had strong historical and cultural associations before the colonial rule. The British, however, implemented a divide and rule policy that considered the Embu to be rebellious and the Mbeere to be more compliant, or rather loyal. These colonial identities were not very neutral, as they created lasting divisions by turning previously related communities into administrative rivals. In the long term, this destroyed the feeling of common identity and replaced it with competition and distrust, which remains in the local politics and memory.

The Mbeere were described as loyalists, yet they were not the greatest beneficiaries of the colonial development. They had less fertile and drier land and consequently had little investment in roads, schools, and agricultural assistance as compared to the Embu highlands and Kikuyu regions. Frequent droughts and lack of land complicated life, particularly without the assistance of the state. Meanwhile, colonialism undermined the traditional forms of leadership, e.g., the councils of elders and age-set institutions, through appointed chiefs who imposed taxes, labour, and colonial laws. This change diminished the power of local systems of governance and created more hatred against the colonial rule.

The Mau Mau Period and the Position of the Mbeere

During the Mau Mau uprising, the Mbeere found themselves in a difficult and often dangerous position. They were often considered loyalists or moderates, and this placed them in the hands of Mau Mau fighters and the colonial administration. Among the most extreme punishments that were administered to some of the Mbeere was ear mutilation, which was done to denote those individuals who were accused of rejecting the Mau Mau oath. Such attacks, mostly committed by insurgents in the neighbouring communities of Embu or Kikuyu, fuelled fear and further segregated communities.

Nevertheless, the fact that the Mbeere were not very much involved in the Mau Mau struggle is deceptive. Archive reports and oral testimonies indicate that most Mbeere were indirectly involved in the movement, in some significant manner or other. They also provided food, shelter, information, and logistical assistance to fighters, particularly during the night. There were coded language and signs that warned of coming colonial patrols, and this demonstrated some degree of organisation and awareness among Mbeere communities. Local elites like Chief Kombo of Mavuria had a mixed role to play, which was de-oathing movements, but also the attempt to protect their groups of people against more severe colonial repression.

Post-Independence Silence and Historical Exclusion

After Kenya gained independence in 1963, the contributions of the Mbeere to the struggle for freedom were largely left out of national narratives. Most Mau Mau histories focus on the Kikuyu, Embu, and Meru, especially those who fought in the forests, while communities like the Mbeere, whose involvement was more supportive than militarized, were overlooked. The colonial label of “loyalists” continued into the post-colonial period and was used to exclude the Mbeere from compensation schemes, public recognition, and political benefits linked to the independence struggle.

This exclusion has had lasting effects. Mbeere areas have continued to lag behind neighbouring regions in infrastructure, education, and economic development. Politically, the dominance of Embu narratives has reinforced rivalry within Embu County, further weakening the earlier sense of shared history. The marginalisation of the Mbeere is therefore not simply a gap in historical writing but an ongoing process that affects development, identity, and political recognition. Including Mbeere experiences in the wider Mau Mau narrative is important not only for correcting the historical record but also for addressing long-standing inequalities rooted in both colonial and post-colonial policies.

Conclusion

The history and cultural identity of the Mbeere people is an example of how marginal communities of Kenya had evolved resilient social institutions with a foundation on language, kinship, and environmental adaptation. Before the colonial interventions, the Mbeere society structured governance, economic production and moral life through clans, ownership of land based on family, age groups and traditional rituals. These structures were disrupted by colonial power by the administrative reclassification, economic abandonment, and the positioning of Mbeere political behavior as loyalist especially in the Mau Mau period, when they were excluded in the historical record of the dominant nationalism.

This exclusion was further enforced by postcolonial politics, uneven development, and media images that still excluded Mbeere voices. By re-centering the history of Mbeere using oral testimony, archival documents, and cultural analysis, the definition of narrow descriptions of resistance is challenged and power is shown to be functioning through quietness, memory, and language. Finally, the Mbeere experience highlights that survival, adaptation and cultural persistence in dry and politically marginal places represented a significant yet often overlooked historical agency in Kenya's general struggle to form identity and nationhood.

Works Cited

Bennett, D., and K. Njama. Mau Mau from Within: Autobiography and Analysis of Kenya’s Peasant Revolt. Modern Printer Paperback, 1966.

Glazier, Jack. Land and the Uses of Tradition among the Mbeere of Kenya. University Press of America, 1985.

Hornsby, Charles. “A Political History of the Embu and Mbeere Communities of Kenya, 1957–2021.” 2022.

Waiganjo, Benson. At the Periphery in Mau Mau Discourse: A Case of the Mbeere of Embu County, Kenya, 1952–2014. PhD thesis, Karatina University, 2022. Karatina University Repository. Web.

Kanyingi, Ben, J. Mwaruvie, and J. Osamba. “The Rhetoric of ‘Speaking in Tongues’ amongst the Mbeere Mau Mau in Colonial Embu.” African Journal of Education, Science and Technology, vol. 6, no. 4, 2021, pp. 262–278.

Kinyatti, Maina wa. History of Resistance in Kenya. Mau Mau Research Centre, 2008.

Makoloo, Maurice. Kenya: Minorities, Indigenous Peoples and Ethnic Diversity. Minority Rights Group International, 2005.

Mwaniki, H. S. K. The Living History of Embu and Mbeere to 1906. Kenya Literature Bureau, 1973.

Roots, Migrations and Settlements of Mount Kenya Peoples: Focus on the Embu Circa 1400–1908. Media Document Supplies, 2008.

Mwaruvie, John. Pre-Colonial Mbeere Economy: Coping Strategies in an Arid Environment. LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, 2011.

Osborne, Myles. Ethnicity and Empire in Kenya: Loyalty and Martial Race among the Kamba, c. 1800 to the Present. Cambridge UP, 2014.

Ray, S. K. Art and Culture of the Mbeere, Embu, and Kamba Peoples of Kenya. UMI Research Press, 1977.

Saberwal, Satish. “Historical Notes on the Embu of Central Kenya.” Journal of African History, vol. 8, no. 1, 1967, pp. 29–38.

The Traditional Political System of the Embu of Central Kenya. East African Publishing House, 1968.

Thatiah, Isaya. Jeremiah Nyagah: Sowing the Mustard Seed. Rizzan Media, 2013