Generation, Governance, and Moral Authority: The Gadaa System among the Borana

Introduction

Borana are Oromo-speaking pastoralists who live in southern Ethiopia and Northern Kenya. Borana people live in arid and semi-arid conditions, and their survival relies on the effective livestock husbandry measures, access to water, and the strong networks of social cooperation. The Gadaa, an indigenous political, social, and ritual system which is structured around generation-sets and age-grades, is at the centre of Borana political, social, and ritual life. Gadaa was listed in the UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2016.

Nevertheless, such understanding does not prevent the Gadaa system from becoming the topic of substantial academic discussion. Past research has tended to emphasize its egalitarian ideals( belief that people are equal and deserve equal treatment and rights) and to raise concern about its effectiveness in practice, especially in terms of differences in age disparities in the leadership communities and the formal barring of women and young people from the position of political office.

Using Borana views and the emerging literature, this article analyzes these characteristics commonly described as structural issues and reveals that they are a part of the rationality, stability, and sustainability of the Gadaa system. This article presents Gadaa as a multi-faceted and dynamic form of politics based on Borana perceptions of time, morality, and social reproduction through examining generation-sets, age-sets, leadership roles, resource governance, and gendered authority.

Borana Social Organization and Worldview

Borana people are essentially pastoral; cattle play a central role in their economy, ritual, and symbolism. The social organization is centered on clans (gosa) and lineages (mana), which are separated into two major groups, and individuals within one group should not marry representatives of the same group, but members of the other group. Sabbo and Goona. Such kinship systems control marriage, inheritance, and involvement in political life.

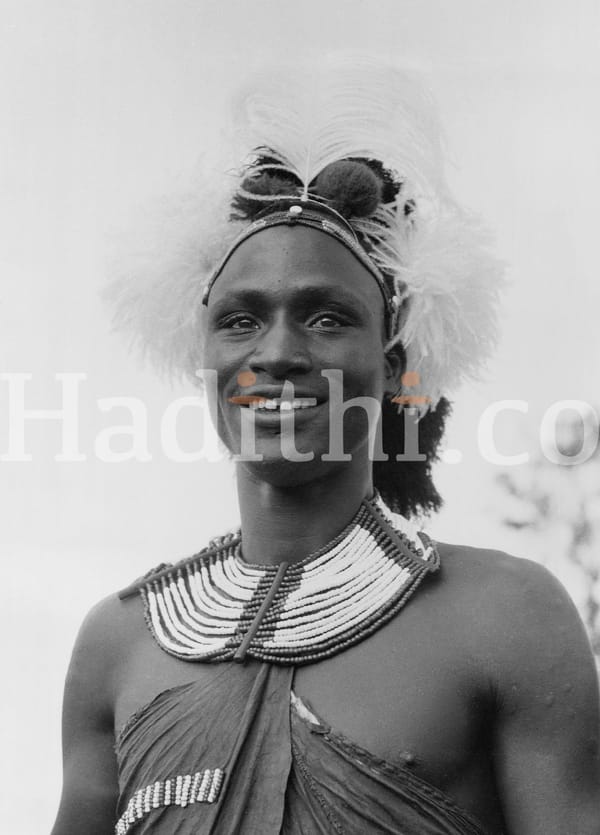

The focus of religious life has always been on Waaqaa, the highest creator, and moral and social order has been directed by safuu, a concept that encompasses ethics, respect, and harmony between man, nature, and God. The custodians of this moral and spiritual order are called Qaalluu, and they give legitimacy to the political authority, as well as guaranteeing that the leadership corresponds to the communal values.

Foundations of the Gadaa System

The Gogeesa Gadaa (Gadaa Class/Party), as a concept to the Borana setting, is the generational, democratic, and socio-political method of governance that is observed within the Borana Oromo community, which extends across southern Ethiopia and northern Kenya. The system has a 40-year cycle with five active and rotating periods of ruling (eight-year ruling period Gadaa classes), which guarantee a peaceful and methodical transference of power, called baallii. The Gadaa classes (Luba) of Birmaji, Horata, Bichile, Dulo, and Robale have their own responsibilities in the government, and the leadership duties change in order.

The 72nd Borana Gadaa power transition ceremony (Baallii) was held from March 5, 2025, to March 9, 2025. The official inauguration and handover ceremony, which marked the transfer of power from the 71st Abbaa Gadaa, Kura Jarso, to the 72nd Abbaa Gadaa, Guyyoo Boruu Guyyoo, a ceremony that has lasted more than 500 years. The ceremony is an example of the democratic and rotational basis of the Gadaa system, which further supports continuity and unity among the Borana communities in both Ethiopia (Oromia region) and Kenya (Isiolo, Marsabit, and Tana River counties).

Gadaa leadership is a voluntary, accountable leadership. The Abba Gadaa (father of the Gadaa) is chosen to serve one term of eight years with no renewal and is in charge of running political, economic, social, and religious matters. Power is maintained by the use of councils, assemblies, and moral persuasion instead of coercion, with the Gumii Gaayyoo being the supreme council that meets after every eight years to discuss and draft laws. Ritual legitimacy cannot exist without political power: the Abba Gadaa cannot be put in power without the approval of the Qaalluu, the hereditary spiritual chief who sanctions authority. The symbols of leadership, like the bokkuu (scepter), reaffirm the ceremonial quality of power, and this integration of government and ritual, and morality in the Borana political system.

The Gadaa system also recognizes the position of women who, even though technically are not part and parcel of the ruling class, have a hand at decision making processe,s especially in matters that relate to the safeguarding of their rights. By bringing together generational rotation, elected leadership, ritual authority, and shared social norms, the Gadaa system demonstrates how Borana society has maintained a sophisticated and adaptable form of governance over time.

The Gadaa Grades

As described by Borana tradition and analyzed by Tagawa, the Gadaa system consists of eight grades, which each generation-set must pass through. Historically, the full cycle required approximately 88 years, later extending to around 96 years due to adjustments in childbearing rules.

- Dabballe (0–8 years): Early childhood. Children are not yet fully recognized as social agents and are referred to by nicknames. They wear a distinctive guduru hairstyle, resembling that of their grandfathers.

- Gamme (8–24 years): Learning phase divided into junior (didiqqo) and senior (guguddo) stages. Boys acquire herding skills and undergo ritual preparation for eventual participation in a generation-set.

- Kuusa (24–32 years): Formation of a new generation set. Six councilors (adula) are appointed. Members are prohibited from marrying and focus on seasonal herding and preparation for leadership.

- Raaba (32–40 years): Warrior stage. Associated with community defense and military duties. Marriage is permitted, but childbearing is traditionally restricted.

- Doorii (40–45 years): Senior warrior stage. Members may begin childbearing and prepare to assume leadership responsibilities.

- Gadaa (40–48 years): Ruling stage. Three of the six adula councilors become Abbaa Gadaa, with the senior leader (Abbaa Gadaa Arboora) holding supreme authority.

- Yuuba (48–72 years): Retirement stage. Former leaders advise successors and participate in rituals supporting the next generation set.

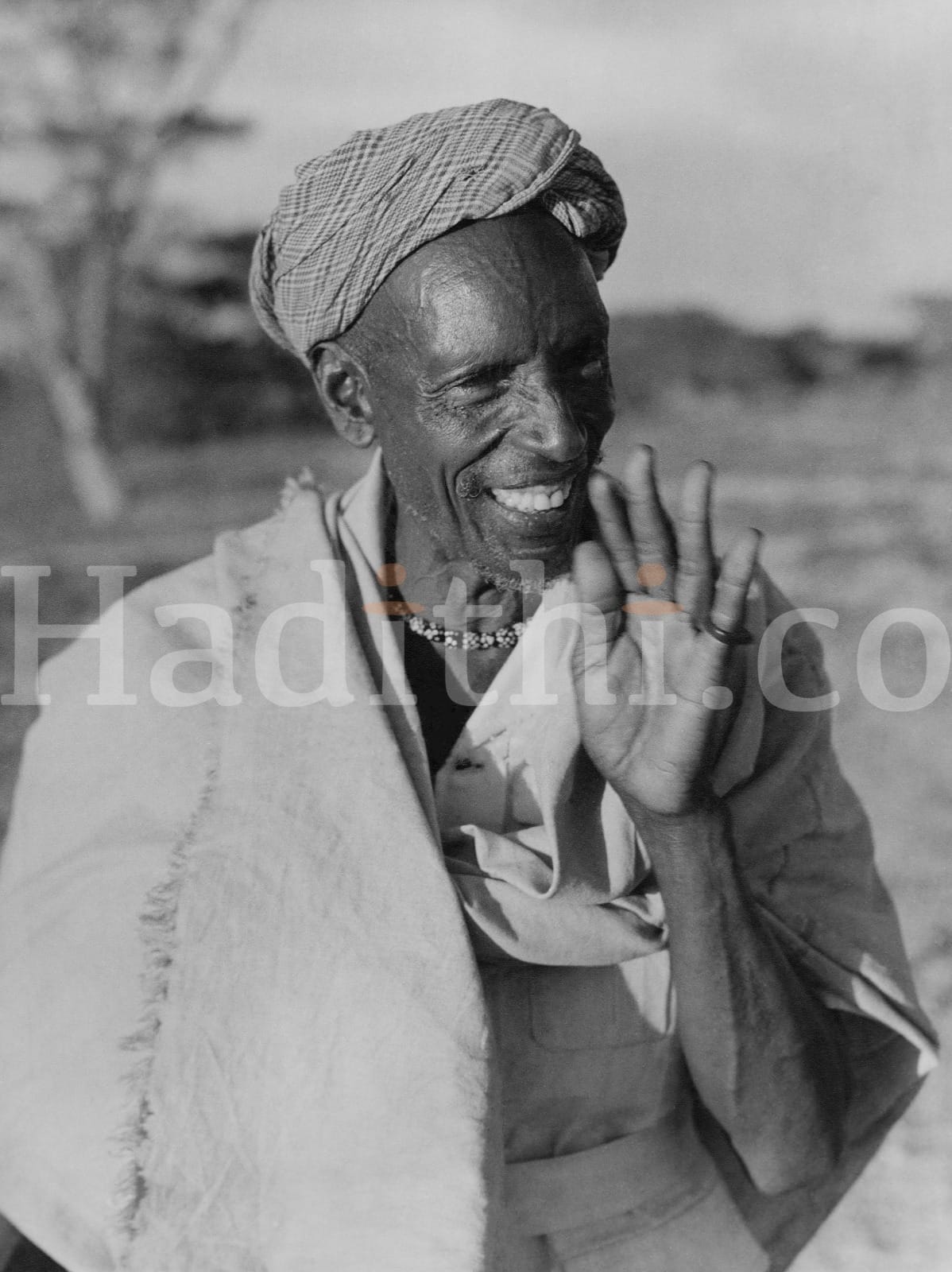

- Gadaamojjii (72–80+ years): Final elderhood stage. Elders complete ritual obligations and serve as jaarsa, moral and social authorities.

All grades must be completed. Borana emphasize that a generation-set has to go through all the phases, either "living or dead", to maintain the ritual continuity and social cohesion

Generation-Sets and Age-Sets

Scholars have long debated age differences within generation sets. Previous studies by Asmarom Legesse and Paul Baxter stated that the continuous introduction of new members causes a considerable age gap, which constitutes a demographic contradiction.

Genta Tagawa disputes this interpretation by putting the focus on Borana explanations:

- Generation-set system (Gadaa): Open, continuous, and cyclical. A generation-set is “born” and circulates indefinitely.

- Age-set system (Hariya): Closed and finite. Age-sets group peers of similar age and eventually dissolve as members die.

From a Borana perspective, age differences are not flaws but structural features that ensure continuity. Late entrants guarantee that ritual and social duties are maintained, even as older members age or pass away.

The Gadaa system also distinguishes between ilmaan korma (“sons of a bull”) and ilmaan jaarsa (“sons of an elder”), which manage intergenerational timing within a generation-set. Ilmaan korma are born when their fathers’ generation set is still active, before reaching the gadaamojji stage. Ilmaan jaarsa are born after the fathers’ generation set reaches elderhood. These categories are temporary: those initially considered ilmaan korma may later transition to ilmaan jaarsa once their fathers enter the elder phase. This temporal flexibility ensures smooth social and ritual continuity, highlighting the system’s adaptability and structural resilience.

Political Authority and Leadership under Gadaa

The Borana Gadaa system has a decentralized and layered political system to prevent too much power concentration. Abbaa Gadaa is the mediator of the dispute, the ruler of the society, and the leader of ritual life, performing the role for eight years. Some of the institutions that support him include the military Abbaa Seera (law), the Hayyuu (council of advisors and judges), and the Gumi Gayo (supreme assembly under the sacred Odaa tree). Consensus is used to make decisions, and leaders who contravene legal (seera) and moral (safuu) issues can be eliminated through buqqisaa.

Ritual power is based on the Qaalluu, who are blessed by and which is continuity across generations. The Gadaa system ensures accountability through segregation of political and spiritual power, a balance in power as well as social order.

Water as Power: Tula Wells and Resource Governance

Water is a central source of authority in Borana society. Deep wells (tulaa) and well clusters (tula-sallan) are vital for survival during droughts. Maintenance involves daily cleaning (naanniga), seasonal sediment removal, and major rehabilitation every few decades.

Key governance roles include:

- Konfi: “Father of the water,” often a hereditary position

- Chora Ella (Well Council): Oversees well management

- Abba Herrega: Supervises daily watering order

- Abba Guyyaa: Assigns watering days

Water access follows a strict three-day rotation system based on clan and lineage rights. Violations are met with exclusion, demonstrating how resource management functions simultaneously as law, authority, and conflict prevention.

Gender and Power: Women’s Exclusion and Parallel Authority

Formal Exclusion from Gadaa Councils

Women are formally excluded from Gadaa councils, which consist exclusively of men who have progressed through the requisite age-grades. This exclusion is often interpreted as patriarchal domination, yet such readings risk imposing contemporary assumptions onto indigenous governance systems.

The Siiqqee Institution

Women exercise authority through Siiqqee, a parallel institution of collective power. Upon marriage, a woman receives a siiqqee stick, symbolizing her rights and social authority. Violations of these rights may trigger Iyya Siiqqee (Ululating scream), Godaana Siiqqee (Protest against injustices or to assert their rights and power), or Abaarsa Siiqqee (Ritual cursing). Men who violate Siiqqee norms risk social censure, including disqualification from leadership.

Women also safeguard safuu, intervening in domestic, inter-clan, or territorial conflicts. Rituals such as Ateetee reinforce women’s voice in community matters, while figures like the Qaalittii (Wife of the Qaalluu) mediate political and ritual decision-making behind the scenes.

Youth, Age, and Delayed Authority

Youth exclusion from formal authority is deliberate. Leadership is granted only after multiple age-grades, ensuring maturity, experience, and ethical grounding. The Raaba stage (ages 24–40) trains young men as warriors and community protectors, while limiting their influence in high-level political decision-making. This gradual preparation emphasizes responsibility, cultural knowledge, and moral discipline, rather than immediate entitlement.

Colonial Disruption and Postcolonial Marginalization

Colonial and imperial administrations profoundly undermined Gadaa governance. In Ethiopia, the late nineteenth-century empire criminalized Gadaa practices, while in Kenya, British indirect rule favored appointed chiefs over indigenous leaders. Limitations on grazing, movement, and resource control further weakened Borana autonomy.

After independence, both states largely retained centralized colonial administrative systems, continuing to marginalize pastoralist communities and subjugate customary leadership structures. Despite these disruptions, Gadaa institutions persisted in modified forms, retaining cultural and moral significance.

Conclusion

The Borana's Gadaa system is a good example of an evolved and adaptive form of governance that combines political power, ritual power, and resource management. It is seemingly structural issues like the age difference, young people lacking in leadership positions, and women not being included in the formal councils, but in actuality, they are all planned aspects that bring continuity, accountability, and social strength. Mechanisms such as ilmaan korma / ilmaan jaarsa and the Siiqqee institution show how the system manages population differences, organizes relations between generations, and upholds moral discipline within society.

Instead of being a historical artifact, the Gadaa still functions as an active institution and can act in response to social, environmental, and political changes. The fact that it has remained relevant over time shows that African societies have come up with contextualised, advanced systems of governance that balance the power, ethics, and the management of resources. Conducting research based on the Gadaa terms, one can understand the different forms of democracy, the control of authority, and interrelatedness between the ritual system, political system, and ecological system in maintaining the social order.

Works Cited (MLA)

Aguilar, Mario. “The Eagle as Messenger, Pilgrim and Voice: Divinatory Processes among the Waso Boorana of Kenya.” Journal of Religion in Africa, vol. 26, no. 1, 1996, pp. 56–72.

Appiah, Kwame Anthony, and Henry Louis Gates Jr., editors. Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford UP, 2010.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. 2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census Volume IV: Distribution of Population by Socio-Economic Characteristics. KNBS, 2019.

Legesse, Asmarom. Gada: Three Approaches to the Study of African Society. Free Press, 1973.

Tagawa, Genta. “The Logic of a Generation-Set System and Age-Set System of the Borana-Oromo.” Nilo-Ethiopian Studies, vol. 22, 2017, pp. 15–25.

UNESCO. Gadaa System: Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. UNESCO, 2016.