AFRICAN GODS: The Orma Tribe of Kenya

INTRODUCTION

The Orma people are a semi-nomadic pastoral community living primarily in Kenya’s Tana River and Lamu Counties. They belong to the broader Oromo family of Eastern Africa, sharing deep cultural and linguistic roots with Oromo communities in Ethiopia. Cattle shape their social identity, economy, and cultural pride. Although many Orma are Muslim today, their spiritual foundation is deeply rooted in ancient indigenous beliefs centered on the Supreme God, Waaqa. Understanding their worldview requires exploring these traditional spiritual practices, which continue to shape their identity, moral values, and relationship with nature.

Language, Identity, and History

The Orma speak the Orma language, an Eastern Cushitic tongue closely related to Borana, though the two languages are not mutually intelligible. Historically, they were referred to as Warra Daya or Wardey, while the term “Galla,” used by outsiders, is considered derogatory and firmly rejected by the Orma today. The name “Orma” affirms their identity and roots along the Tana River, distinguishing them from neighboring groups such as the Somali.

Historically, the Orma migrated southwards from the Horn of Africa, settling along the Tana River as pastoralists seeking grazing lands and stable water sources. Over generations, they developed social structures, rituals, and spiritual systems that tied their lives to cattle, rain cycles, rivers, and the land. Despite pressures of displacement, conflict, and assimilation, the Orma have preserved much of their cultural identity while adopting Swahili as a second language for broader communication.

Waaqa Guraacha — The Supreme God

At the center of Orma spirituality stands Waaqa Guraacha, known as “The Black God.” This title symbolizes his mystery, purity, and infinite nature rather than physical color. Waaqa is believed to be the eternal creator, all-knowing, all-powerful, pure in goodness, and the source of justice and truth. He created all existence: the sky, the waters, the land, the stars, animals, and human life. Cattle, which symbolize wealth and sustenance, are considered sacred gifts directly from Waaqa.

Oral tradition teaches that Waaqa once lived among people but withdrew into the heavens after humans violated the moral order. This created spiritual distance, yet left pathways for communication through nature, breath, and blessings like rain and milk.

Saffu — The Divine Moral Code

A key pillar of Orma spirituality is “saffu,” a sacred moral law guiding relationships between people, animals, land, and God. Upholding saffu means honoring truth, kindness, respect, and harmony. Violations of saffu, such as injustice, greed, mistreatment of animals, or breaking social taboos, are believed to disrupt cosmic balance and invite misfortune — drought, illness, conflict, or famine. Thus, morality is not merely a social responsibility but a cosmic one — a way to preserve Waaqa’s intended order.

Examples of upholding saffu include:

- Treating cattle gently and never cursing them.

- Honoring elders and respecting age-set roles.

- Helping strangers, travelers, and the vulnerable.

- Respecting communal grazing boundaries.

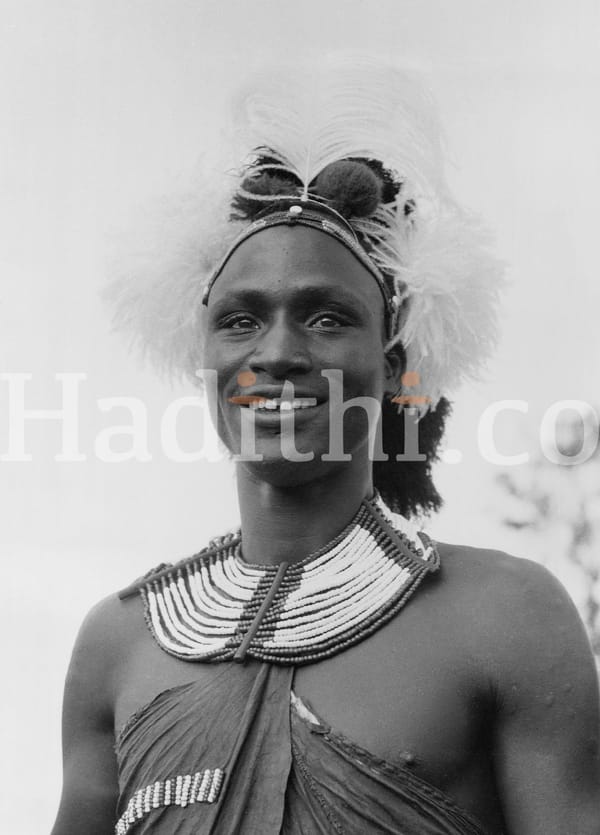

Ayyaana — Spirit Messengers of God

While Waaqa remains in the high heavens, his presence is felt on earth through Ayyaana, spiritual forces assigned to each person, place, and clan. Ayyaana guides destiny, heals, protects, and intervenes when balance is threatened. Certain individuals, known as Qaalluu, are gifted with the ability to communicate with these spirits, serving as priests and advisors. They interpret dreams, perform blessings, lead rituals, and preserve community ethics.

The Sacred Role of Women — Ateetee and Maaram

Women hold a sacred position in Orma spirituality through female divinities such as Ateetee, the goddess of fertility, childbirth, and family well-being. Her rituals, performed exclusively by women, involve sacred prayer songs, ceremonial dancing, and the symbolic use of milk and butter for blessing and purification. Another revered feminine spirit is Maaram (or Ayyo Umtuu), guardian of waters and oceans. Women seeking children or safe pregnancies offer prayers near rivers or wells, believing that spiritual and earthly fertility are connected through Maaram’s protective power.

Booranticha — The River Spirit of Cattle

For the Orma, rivers are sacred beings. Among them, Booranticha is a powerful river spirit who protects cattle — the essence of Orma wealth and survival. Families gather at riverbanks with offerings such as milk, blessed bread, local beer, or grain to honor Booranticha, especially before migrations or during drought. These rituals reinforce the spiritual bond between people, cattle, and the waters that sustain them.

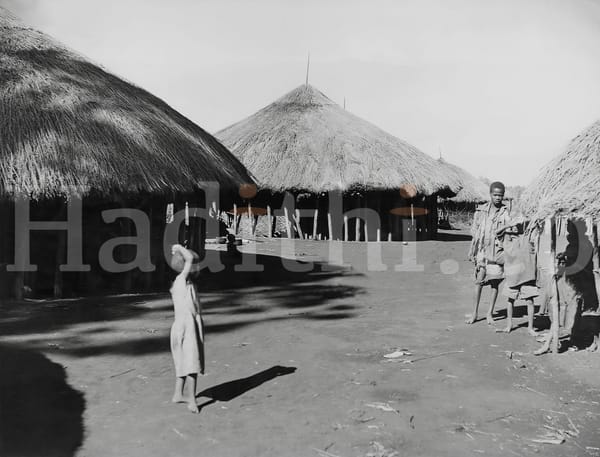

Galma — Sacred Worship Spaces

Orma rituals take place in designated sacred spaces called Galma — structures built in hidden groves near hills, large trees, or flowing rivers. Inside Galma, community members unite through chanting, rhythmic drumming, blessings, and spiritual possession ceremonies. Cleansing rituals remove misfortune and restore saffu. Before major travels or significant cultural events, herds are presented for divine blessing. Cultural purity rules apply; for example, menstruating women traditionally refrain from entering Galma to maintain the spiritual purity of the space during rituals.

Social Structure and Spiritual Order

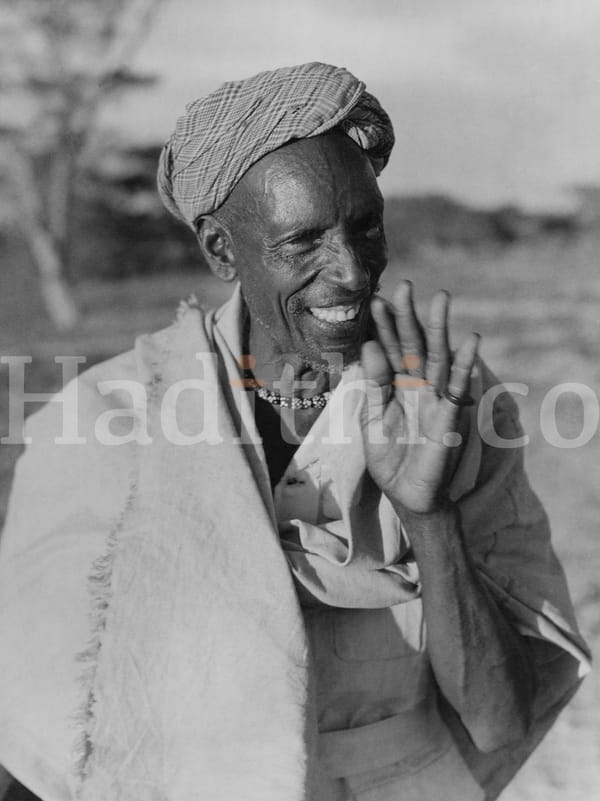

Orma spirituality is intertwined with social structure. Elders hold authority in spiritual matters, managing disputes, blessing migrations, and interpreting saffu. The age-set system shapes responsibilities, leadership, and moral behavior. Clans carry specific rituals, totems, and Ayyaana associated with their lineage. Through these structures, spirituality is not separate from daily life — it is the foundation of community order.

Creation and the Origin of Humanity

Orma creation stories describe a world that began with water. Waaqa separated the sky from the waters, drew forth land from below, and commanded light to part from darkness. Humans were then formed as sacred caretakers of creation. Some narratives mention the first human named Horo; others describe a single being divided into man and woman so that life could multiply. Across all versions, humanity is seen as a direct extension of Waaqa’s purpose — entrusted with guardianship, not domination.

Modern Faith: Islam and Indigenous Beliefs Together

Today, Islam plays a central role in Orma life, guiding daily prayer, social structure, and education. Yet indigenous spirituality remains alive beneath the surface. Concepts like saffu are still powerful in judging right and wrong; cattle rituals continue to reflect older beliefs; and references to Waaqa are made even in Islamic contexts. Many communities combine Islamic prayers with older rituals, creating a harmonious cultural duality that respects both ancient heritage and modern devotion.

Examples of this blending include:

- Blessing cattle with both Quranic verses and traditional chants.

- Using saffu to evaluate moral behavior.

- Referring to Waaqa alongside Allah.

- Performing rain-calling rituals rooted in pre-Islamic belief.

Challenges in the Modern Era

Modern Orma communities face challenges such as shrinking grazing lands, climate-related droughts, conflicts with neighboring groups, and pressure on traditional rituals and language. Despite these pressures, cultural revitalization efforts, documentation, and community leadership continue to protect Orma identity and spirituality.

Conclusion

The traditional beliefs of the Orma tribe reveal Africa’s deep spiritual legacy — one that recognized a single creator God long before global religions expanded into the continent. Their faith in Waaqa, their reverence for women’s sacred power, and their moral commitment to saffu reveal a worldview in which nature, humanity, and the divine remain inseparable. Even as Islam shapes their modern identity, the Orma continue to honor the wisdom of their ancestors. Their prayers rise each dawn with the hope that Waaqa’s presence still watches over the cattle, the rivers, and every soul who walks under the vast sky of Tana River.