Rũracio, ũthoni, and the Social Foundations of Agĩkũyũ Marriage

Introduction

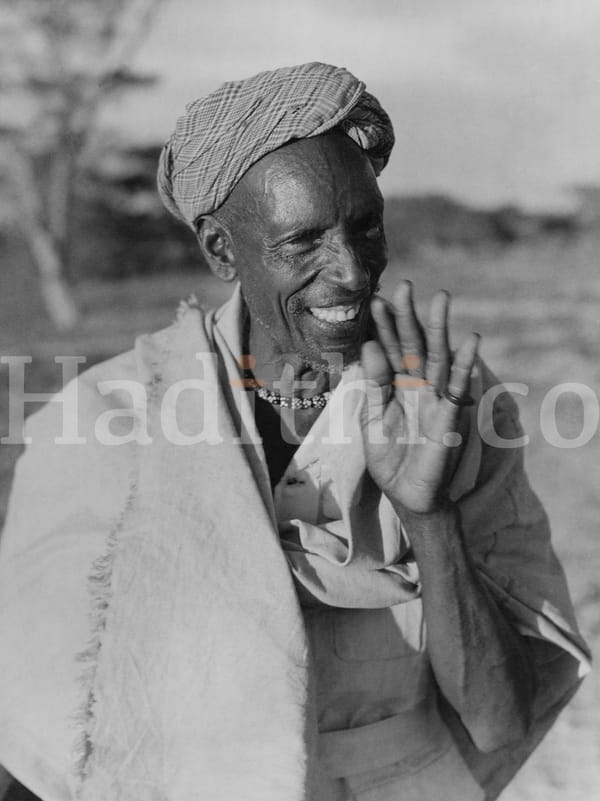

Marriage among the Agĩkũyũ (Kikuyu) people of central Kenya is far more than a union between two individuals; it is a deeply communal institution that binds families, lineages, clans, and even broader communities together. Unlike the individualistic, romantic model common in Western cultures, Agĩkũyũ marriage has historically been a structured social process designed to strengthen kinship networks, ensure economic stability, transmit cultural values, and create lifelong alliances known as ũthoni (in-law relationships). At its core lies Rũracio, often acknowledged as “dowry” or “bride price,” but better understood as a gradual, symbolic exchange of gifts that demonstrates respect, responsibility, and long-term commitment between families.

Rũracio is never seen as buying a woman. Instead, it serves as a culturally prescribed way for the groom’s family to prove they can support the new household, honour the bride’s family, and build a relationship of reciprocity that endures across generations. In traditional society, marriage marked full adulthood: a married man gained authority over a homestead. In contrast, a married woman ensured continuity for both the family she was born into and the family she joined through marriage, by bearing children and strengthening ties between the two families.

Through ũthoni, the two families became bound to support one another in celebrations, crises, and everyday life, creating one of the most effective social safety nets in pre-colonial Agĩkũyũ society.

Although Christianity, formal education, urban migration, cash economies, and modern legal frameworks have reshaped many practices, the core principles, consent, gradualism, elder oversight, and mutual respect continue to guide many Agĩkũyũ families today. This article traces the classical form of the process while noting key contemporary adaptations.

Agĩkũyũ Origins and the Cultural Foundations of Marriage

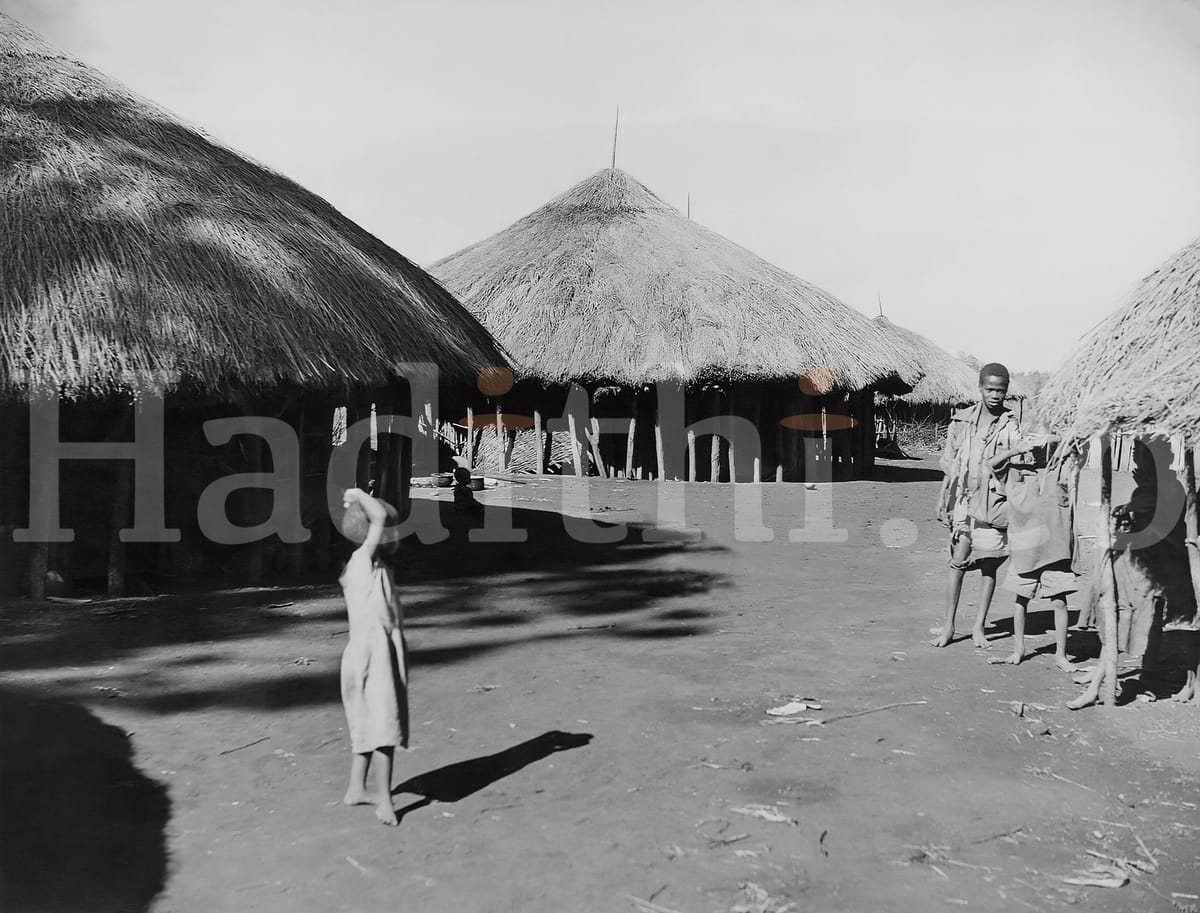

The Agĩkũyũ marriage and dowry (Rũracio) system is built on their origin story, which explains why unions must follow certain rules and why the process is so careful and communal. Ngai (God) created the first couple, Gĩkũyũ and Mũmbi, and placed them at Mũkũrwe wa Nyagathanga in Murang’a County. This place is considered the spiritual birthplace of the Agĩkũyũ people, from where families spread across central Kenya.

Gĩkũyũ and Mũmbi had nine daughters. These daughters, Wanjirũ (Anjirũ), Wambũi (Ambũi), Njeri (Aceera), Wanjikũ (Anjikũ), Nyambũra (Ethaga), Wairimũ (Airimũ), Waithĩra (Aithĩrandũ/Angeci), Wangarĩ/ (Angari), and Wangũi (Angũi), with Aicakamũyũ (Warigia) sometimes counted as the tenth, became the founding mothers of the nine (or ten) main clans (mihiriga), which are symbolically referred to as “kenda mũiyũru” or “nine full clans” linked to the Agikũyu custom belief that avoids directly counting people, as that was believed to bring bad luck or death.

Clan names come from the mothers (matrilineal naming), but inheritance of land, property, and social duties pass through the male line (patrilineal descent). This mix of matrilineal clan names and patrilineal descent directly shapes marriage and Rũracio. People cannot marry within the same clan(mũhiriga) to prevent misfortune or conflict, but since sub-clans (mbari) are named after male ancestors like grandfathers or the husbands of the daughters, this allows useful alliances.

When a young man wants to marry, he tells his father, who asks the council of male elders to check the girl’s clan for compatibility and her family’s reputation. Senior Chief Mbure stresses that this check is essential, as marrying into a forbidden or mismatched clan could cause problems. Only after approval does the formal process start, with no gifts or visits until lineage suitability is confirmed. In this way, every marriage repeats the original pattern: just as Gĩkũyũ and Mũmbi’s daughters married outside their circle and helped grow the community, today’s marriages create alliances, ensure family continuity, and bring prosperity. Rũracio is the respectful, step-by-step way families honour this sacred tradition and bless the new union.

Kinship Structure and Family Roles in the Dowry Process

Agĩkũyũ society is organised in nested kinship units. The smallest is the mũcĩĩ (homestead or household compound), typically headed by a man and including his wife or wives, their unmarried children, and sometimes dependents. Historically polygynous, each wife had her own nyũmba (hut), granting her semi-autonomy within the larger homestead.

Land among the Agĩkũyũ is organised through family and clan structures. A mbari/sub-clan is a group of related homesteads that functions as the main unit for owning land and making decisions about it. Land within a mbari is usually passed down from father to son. Several mbari together form a larger group called a mũhiriga, or clan, which connects extended families through ancestry and shared responsibilities.

When a son reaches marriageable age and identifies a woman he wishes to marry, he informs his father. The father responds with the question: “Where have you seen the woman you want to marry?” This marks the start of formal involvement. The father then consults senior men in the mbari(sub-clan) to investigate the prospective bride’s clan/mũhiriga, family character, and any existing disputes. If approved, the process advances.

Traditionally, the father (or a senior male relative if the father is deceased or unable) bears responsibility for paying Rũracio on behalf of his son. Senior Chief Mbure explains that in the past, the young man did not personally carry goats or money to the bride’s home; he handed them to his father, who then went with other respected elders. In earlier days, full dowry steps were never completed in one day, and every mũhiriga has its own variations on how kũhanda ithĩgĩ is performed.

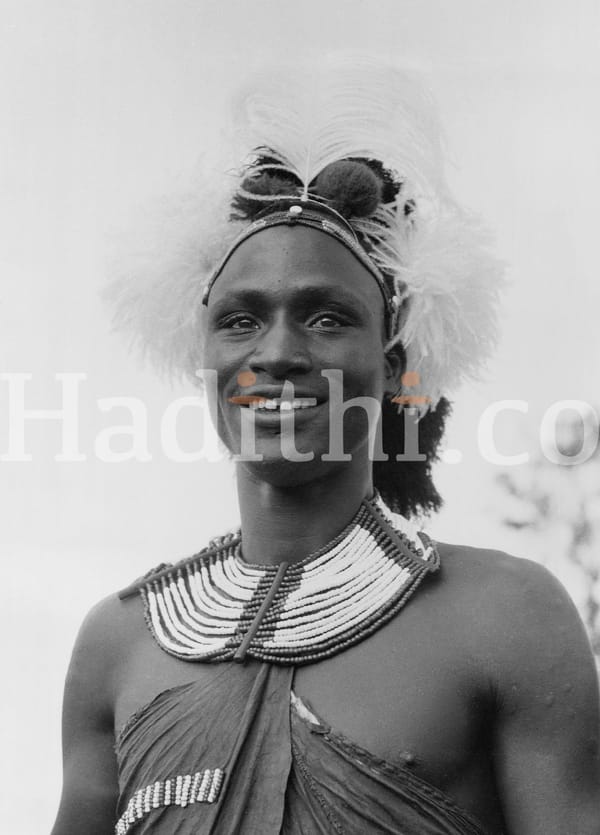

The groom’s delegation returns, bringing mwatĩ na harika, a young ewe/sheep and she-goat that has never given birth, symbolising purity and new beginnings. Quantities and additional items depend on the bride’s mũhiriga. Senior Chief Mbure explains that mwatĩ and harika mark the start of true ũthoni wa mũgĩkũyũ; families do not specify exact quantities for the entire ũthoni, but they do tell the groom what is required for these animals(Mwatĩ and Harika), varying by clan. After presenting them, whatever else was brought is given freely.

A branch or small tree is ceremonially planted in the bride’s compound, witnessed by both families as a visible community signal: she is spoken for. In cases where they have lived together for a while or pregnancy, kũhanda ithĩgĩ may be skipped or postponed until after birth. Senior Chief Mbure notes that traditionally, if a couple had already lived together for a while, they would skip this step after kũmenya mũcĩĩ. Today, some perform it even after a year of cohabitation, which he questions since the original purpose was to notify other suitors that the woman was taken. The symbolic booking is less necessary when the couple is already living together, and the pregnancy publicly demonstrates commitment.

Kũhanda ithĩgĩ shifts the relationship from private courtship to public engagement under family and elder oversight.

Stage 3: Rũracio – The Gradual Payment of Bridewealth

Rũracio forms the heart of the marriage process: a prolonged, multi-visit exchange of bridewealth. Senior Chief Mbure repeatedly stresses that it is never meant to be completed in one day or lump sum “mûracia ûmwe ûtatîîra” reminds that rushing undermines the relationship-building purpose.

After kũhanda ithĩgĩ, the groom’s side returns, led by the father or senior male representative of the groom’s family, carrying livestock (mainly goats and sheep), honey, traditional brew (njohi), and increasingly in modern times, cash equivalents.

A pivotal moment is kuunirwo miti (“being told the requirements”). The bride’s family consults privately and presents a list mirroring what the bride’s father paid as dowry for his wife. If he gave ten goats and two drums of honey, he may ask roughly the same for his daughter; the same standard applies across multiple daughters for fairness. Senior Chief Mbure describes how, in old days, the bride’s father based his demands on what he himself provided for his wife; whatever he was asked then is what he asks now.

If the bride’s father never paid Rũracio for his own wife, custom dictates that he is not entitled to retain any of the bridewealth received for his daughter. Instead, all items must be transferred directly to the wife’s family. In such cases, tradition further requires that the received items must not spend the night in the father’s homestead; they are to be passed on immediately. This rule reinforces generational accountability by ensuring that obligations left unpaid in one generation are settled through the next, thereby maintaining moral continuity, fairness, and respect within the kinship system.

Payments unfold over multiple visits, each treated as a separate event(usually a separate day). For those who paid in lump sum, stepping outside and re-entering the compound was counted as a new day, requiring additional gifts or brew.

If payments are made in a lump sum today, elders may still insist on multiple visits for fairness and discussion.

Alcohol for the men (athuri) is especially important; sharing njohi seals agreements and builds goodwill. The animals are collectively called mbũri cia mirongo (The core goats, typically totalling in tens, which are negotiated and paid in instalments to symbolise the formal bride price), including mwatĩ na harika (often already given), additional livestock, clan-specific animals, and sometimes a fattened ngoima for ritual slaughter.

Senior Chief Mbure emphasizes that the father or elders from the groom's side traditionally carry these items; the young man does not personally deliver them. Today, when young couples handle everything without elders, dowry payments may be seen as just gifts to the bride’s family rather than obligations, he says “ucio ti ũthoni” (that is not true ũthoni), real ũthoni requires the presence of parents and elders, that is, atumia na athuri from both sides.

If the groom’s father was unable to pay Rũracio because of hardship or lack of resources, women’s kamweretho (mutual support) groups would help by contributing money or items. However, tradition still required that the groom’s father personally present the Rũracio to the bride’s family. The women’s support is meant to assist him, not replace his role, so that the father remains the recognised representative of his family in the marriage process.

The drawn-out nature allows families to strengthen bonds, resolve issues, and reaffirm commitment. Requirements vary by mũhiriga, and elders ensure balance. After completion, Senior Chief Mbure reminds us: “ũthoni ndo higagwo” (ũthoni is not closed), the relationship endures lifelong.

Final Rituals: Gûrario/Kûguraria, and Lifelong ũthoni

With Rũracio items delivered over time, final ceremonies conclude the process and fully integrate the bride into her husband’s family.

gûrario, the climax of the marriage formalisation, often serves as the high point. It involves elaborate rituals and the presentation of both indo cia mûthuri (items for the groom’s/husband’s side) and indo cia mûtumia (items for the bride’s/wife’s side). Indo cia mûthuri, brought by the groom to the bride’s family, include ceremonial livestock such as ngoima (fattened ram), thenge (he-goat), ng’ondu (sheep), mori (heifer), njohi ya ûûki (honey beer), blankets, and assorted items for the bride’s father, as well as mbûrĩ cia mîrongo (goats counted in tens). Indo cia mûtumia, related to the bride’s household role, include nyungu (pot), ciihuri (calabashes), ithanwa (axe), mûkwa (new rope), and nguo cia atumia (women’s clothing). Mwatĩ na harika (young virgin goat and sheep) signify the bride’s purity, while mwatĩ ya kiria (a ewe) may be slaughtered to mark completion.

A goat (frequently the ngoima) is slaughtered sometimes at night so meat can be prepared for the following day’s gûrario, symbolising the bride’s full integration into her husband’s lineage. Clan-specific animals (mbûri cia mũhiriga) may be involved, varying by custom.

Kûguraria (“confirming” or “final buying”), the groom presents household items requested by the bride’s women: lesos (khangas) for female relatives, face towels, large sufurias (cooking pots), blankets, and other essentials. These items are used on that day. Senior chief Mbure notes that many today do this incorrectly; traditionally, kuguraria comes after full ũthoni/Rũracio completion and requires time and care.

A key ritual during gûrario is Gũtinia Kiande (“cutting the shoulder”). After the ceremonial goat is slaughtered, elders separate the shoulder joint (kiande), which is served to the bride by her mother-in-law or a senior woman. This act symbolises the bride’s full acceptance into the groom’s family, her assumption of official responsibilities in the new household, her social maturity, and the completion of Rũracio. In practical terms, Gûtinia Kiande functions as the equivalent of a modern marriage certificate: once it is performed, the marriage is publicly and permanently recognised by the community. Because this ritual is irreversible, a man is expected to take time before reaching this stage, carefully ensuring that the union is right, as the woman is thereafter fully acknowledged as his wife and can no longer be claimed by her natal family. Although distinct, Gũtinia Kiande is integral to gûrario, as it secures communal recognition, legitimacy, and blessing of the marriage.

Adaptations and Challenges

Modern realities, urbanisation, Christianity, cash economies, and legal marriage have transformed Rũracio. Lump sum payments, elder exclusion, and cash replacing livestock are now common. Some families demand excessive amounts, turning Rũracio into a financial burden.

Senior Chief Mbure advises that young couples should not manage the process without involving parents or elders, phrasing it as “ucio ti ũthoni.” True ũthoni requires atumia and athuri from both sides.

Despite these changes, many families still honour core values: voluntary consent, gradualism, elder guidance, and mutual respect.

Conclusion

The traditional Agĩkũyũ Rũracio process is a deliberate journey: from a young man’s interest and clan verification, through kũmenya mũcĩĩ / Njurio, kũhanda ithĩgĩ, extended Rũracio negotiations, to gûrario/ kûguraria, and lifelong ũthoni. Each stage carries symbolic depth, reinforces ethics, and builds social connections between subclans and clans in the Kikuyu community.

Far from a purchase, Rũracio expresses: “We can care for your daughter; we honour you; we wish to become one family forever.” Practised with patience and integrity, it fosters resilient networks that have sustained Agĩkũyũ society for generations.

REFERENCES

- “Exploring the Rich History, Traditions, and Lifestyle of the Kikuyu Community.” YouTube, uploaded by Hadithi Africa, premiered 12 Feb. 2026, https://www.youtube.com/@HadithiAfrica.

- Kabetu, M. N. Kĩrĩra kĩa Ũgĩkũyũ (Customs and Tradition of the Kikuyu People). 1st ed., 1947.